TheUltimateDropper CS 175: Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Video

Project Summary

The goal of this project is to create an AI that can play the map The Dropper by Bigre. In the map, the player must complete 16 different levels (of which we focus on the first four); in each level the agent starts off at the top of a large drop and must control themselves as they fall—with the goal of landing safely in water located at the bottom of each level. Each level increases in difficulty by adding more blocks and structures the agent must avoid hitting along with changing the position, direction, and shape of the water. One of the key features we set for this project was to create an A.I. that plays as if it were human, that is, no instantaneous movement, it is unable to see the entire map, and it can only perform an action 4 to 5 times per second (simulating human reaction time). The model for the A.I. uses a convolutional neural network that receives information about the blocks surrounding the agent and outputs q-values for the action to take (N, S, E, W, or no action). The reward the AI receives is proportional to the distance travelled from the start of the drop but gets a huge positive reward for safely landing into water or a huge penalty for hitting an obstacle.

Approaches

Overview

In our status report we had the lofty goal of creating a general purpose A.I. that could play any of the Dropper levels, but due to the large observation space required for such a task, along with the water position changing shape and orientation between levels, we quickly realized that there would not be enough time to train a general A.I. The time was especially limited since each 1000 episode run took 12 hours or more to complete, making the multi-thousand episode training required for a general A.I impractical given our time frame.

In initial testing, we trained an agent such that between each episode, the level was changed, in the hopes that it would generalize and learn how to play all of them, however, we instead found that after a point no improvement was made. We believe this happened both because not enough time was given for training and that better training examples were needed (such as a procedurally generated map that has more variation in its obstacles, however, this was impractical to do on the scale of the map we are playing on). Due to these reasons, we decided to train an A.I. for each individual level, requiring much less training time and far better results.

Observation Space

The observation space we settled on is 15x15 blocks wide and 100 blocks deep, and while 100 blocks deep may initially seem too big, the player falls that distance in only ~3 seconds, and with continuous movement enabled, that much time is needed to avoid incoming blocks. The observation space was reduced to contain only three values: air, water, and anything else (0, 1, and 2 respectively). This simplified the training for our A.I. so that it can easily detect blocks to avoid and the water to target.

Baseline

Our baseline approach was a random A.I. on each level, which basically always failed once reaching the first obstacle. This happens because when using continuous movement, the agent hardly has any time to move in the fifth of a second between actions, so the net effect is that the agent stays roughly in its initial position. This behavior can be good or bad depending on the map, with some requiring large movements and others requiring small changes in position.

Our Model

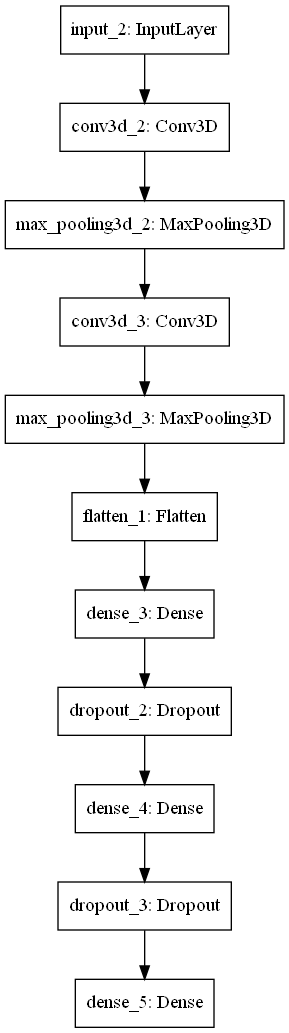

The model chosen is a convolutional neural network that takes in the observation space (blocks), and outputs five probabilities (q-values) for which action to take (N, S, E, W, and no action). The model consists of two convolutional layers each with max pooling, and three dense layers, with the last dense layer being the action q-values. This was chosen both by looking at networks created for similar purposes (specifically the Atari Breakout A.I. in the Keras documentation), and through trial and error. A diagram of the model layers is seen below.

The model was trained using an epsilon greedy algorithm wherein the action made start off mostly random, and slowly over time the model takes over in chosing actions.

Reward Function

To reward the agent during training we took into account four factors: the vertical distance traveled from the starting position rDist, the distance between the agent and the nearest block of water rWater, the number of solid blocks surrounding the player in a 10x6x6 cube rBlocks, and if the player was in the water or not rInWater. We then took a linear combination of these factors as our reward function:

\[R(s) = 4*rDist + 2000*rWater -5*rBlocks + 100000*rInWater\]While the weights of \(R(s)\) could use more tweaking (especially as the water moves between levels), it was still able to generally guide our agent in the correct direction, with it heavily encouraging the agent to move toward water, discouraging the agent from having blocks nearby (hence the negative weight for rBlocks), and a huge reward for making it into the water.

Evaluation

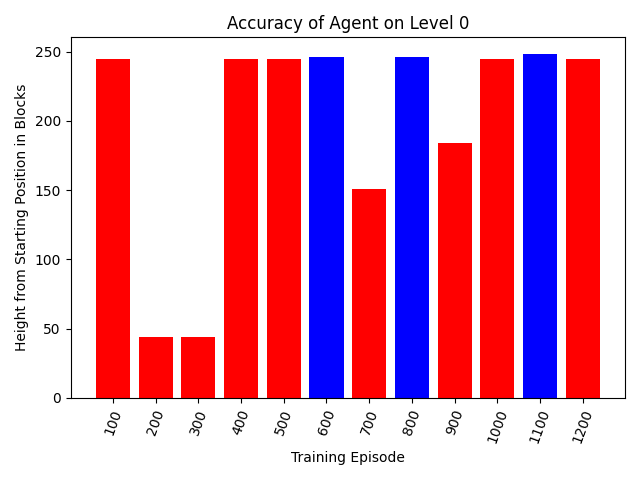

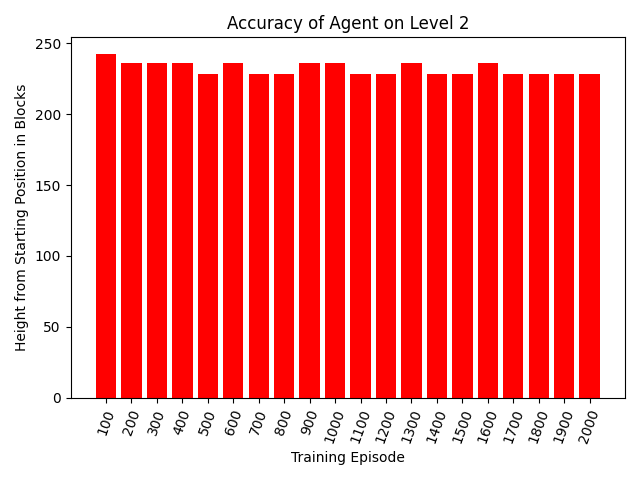

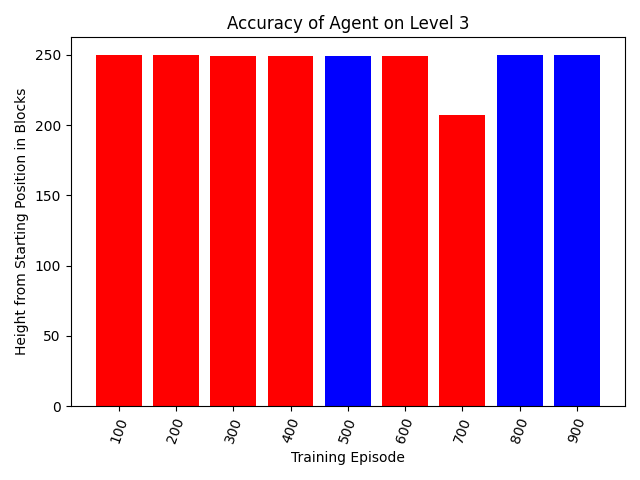

Due to the difficulties in making a general Dropper A.I described above, we transitioned to training a new A.I. individually for levels 0 through 3. Below are discussion and details for each level. For each level, we have a graph showing how far the agent gets at each 100th episode of training, without any randomness (meaning the agent will always take the same path at that episode), with the bar being blue if it landed in the water and red otherwise.

Level 0

Level 0 is the simplest level by far, with an agent winning by moving slightly to the left (which can be seen in the video). From the graph we can see that by episode 600 the agent had learned to land in the water, with it becoming more common as training continued. The graph is fairly noisy because of the structure of the level, where an agent can get all the way to the bottom but not land in water by simply not moving, which explains the initial bump at 100.

Level 1

Level 1 was difficult to train because the water is not directly on the ground as with the other levels, but instead on the side of the map (as seen in the video). Due to this we were not able to train an A.I. that got anywhere near the water so we decided to leave it out and focus on the following two levels.

Level 2

Level 2 for a human looks simple, as it is basically a big funnel, but is actually harder than it initially seems. From the graph we see the A.I. would get near the bottom, but never quite make it to the water. This is because the A.I. learned very early on to move away from the wall it starts in front of, but problems arise when it then continues this and ends up hitting the opposite wall before making it into the water. We believe this could be fixed by punishing the A.I. for purposely getting closer to a wall, but again due to time constraints we did not have enough time to train an A.I. with this implemented.

Level 3

Level 3 is challenging in that the agent must start moving toward the water much higher up than previous levels, again showing that an observation depth of 100 blocks is necessary to finish levels such as these. It is of note that even at only episode 100, the agent had learned to move away from the wall, allowing it to get all the way to the bottom of the map. However, it took until episode 500 for it to learn to move away further as to cover the distance needed to land in the water, and not until 800 that this was being done consistently.

Conclusion

From these four examples we see that our model is able to learn the specifics of widely different levels in around the same time frame. While it would have been more impressive to create a general A.I., it can be argued that this approach is more realistic to how a human would play it, as most people play a specific level over and over until they pass, and then move on to the next again starting from scratch. Given more time we believe that A.I.s for all levels could have been done and given even more time a general A.I. could be trained, but overall the A.Is performed far better than random and could be made even better with more tweaking.

References

Chapman, Jacob, and Mathias Lechner. “Keras Documentation: Deep Q-Learning for Atari Breakout.” Keras, 23 May 2020, keras.io/examples/rl/deep_q_network_breakout/.

Microsoft. “Project Malmo Documentation.” Project Malmo, microsoft.github.io/malmo/0.17.0/Documentation/index.html.

Sharma, Adiyta. “Convolutional Neural Networks in Python.” DataCamp Community, 5 Dec. 2017, www.datacamp.com/community/tutorials/convolutional-neural-networks-python.